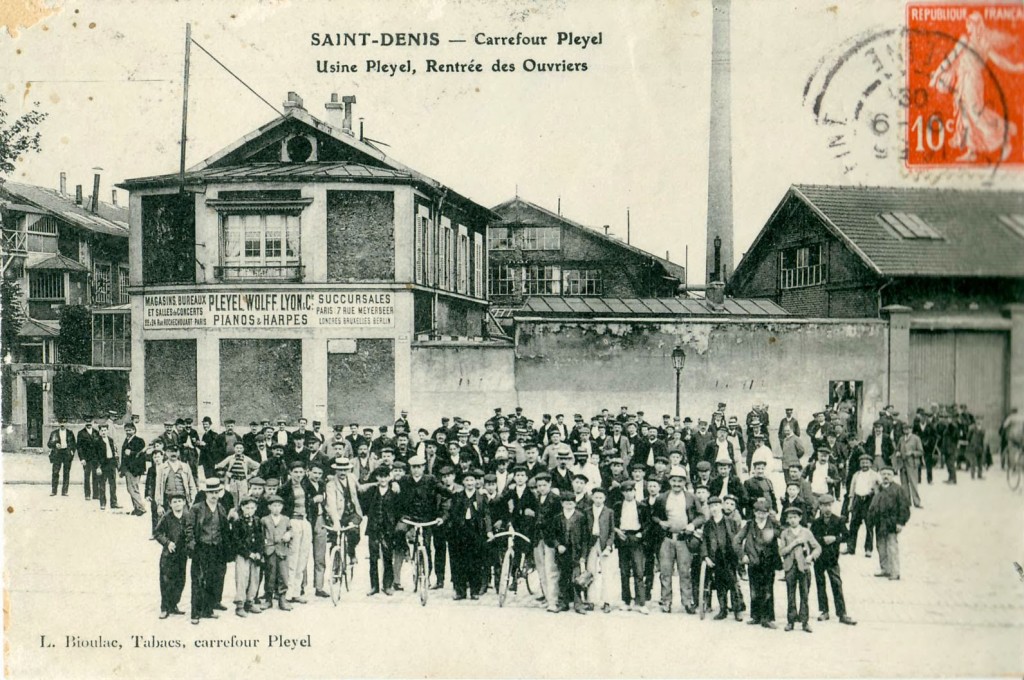

This news spread quickly beyond the borders of France and aroused a bevy of commentators to voice their feelings. Many lamented increased global competition (especially from inexpensive offerings from China and Korea but also from Japan’s high-quality Kawais and Yamahas); some cited the growing appeal of digital keyboards; others faulted the “anti-business atmosphere in France”; and still others blamed Pleyel itself for pursuing a business strategy that did not match the times.In France, this announcement was met with both sadness and dismay: it is “the death of a symbol” and, additionally, it coincides with a long list of recent layoffs in France’s craftsmanship sector with “…tens of thousands of industrial job losses expected in the coming months,” according to Industrial Recovery Minister Arnaud Montebourge (in Telegraph).

For me, as I intimated above, the news enveloped me in a pensive sort of sadness, perhaps strange for someone who doesn’t play the piano. Although ten years of piano lessons—as an adult, along with my daughter—instilled in me a love for the instrument, all of those memorable Monday evenings with lessons from an exceptional teacher and a dear person—Alice McNabb—could not overcome my utter lack of musical talent.

Still I don’t want the traditional piano to disappear from living rooms and school stages, or become anything other than a permanent fixture in concert venues. I recalled reading that Harrods had closed its piano department this year, after gracing the famous department store for 118 years, and I’ve long known that piano sales in both the United States and Britain had been sliding downward. And, now, the renowned Pleyel piano will cease to be made. I couldn’t stop thinking about it.

My friends were perplexed at my sudden interest in Pleyel pianos and even I had to confess that I couldn’t fully explain it. A confluence of several subjects had occurred in my mind, I suppose, and reawakened some dormant dreams. I thought of how, from the time I was in high school and hung out with my musician friends, that I wished I could play the piano and how I envisioned I… would someday. Now know I won’t–another aspiration jettisoned as the years have passed. I thought of how I used to imagine our own piano being played more than it is, and how I wondered if it ever would be or whether I should abandon to this vision. I contemplated how I nearly ensured that it would never again be played in our home.

I thought of The Piano Shop on the Left Bank: Discovering a Forgotten Passion in a Paris Atelier by Thad Carhart, one of my favorite books and one that I devoured on one of our trips to Paris and Provence. It is about Paris, pianos, friendship, and long-held dreams. It is the story of the author’s serendipitous noting of a modest sign for a piano shop that eventually leads to a completely unanticipated path in his life. Ah, maybe this all sounds too melancholic and a bit far-reaching, but the truth of the matter is that I couldn’t stop thinking of these things and that I soon found myself on a very interesting path I hadn’t expected.

That small article that caught my eye—on page 3 of the second section of the Wall Street Journal –propelled me to place a telephone call to my piano tuner Peter Poole: “Have you ever tuned a Pleyel?”

Although Poole has been tuning pianos for over twenty five years, I didn’t really expect that he had crossed paths with a Pleyel here in New England. They still grace the living rooms of many families in Europe, especially France, but are rarely found in North American homes.

In its heyday, Pleyel had an annual production of about 3,000 pianos a year. In 2000, the output fell to 1700. In 2007, Pleyel shifted from a portfolio that included upright pianos to one that focused exclusively on luxury grand pianos priced from €40,000 to €200,000. As the Wall Street Journal story explains, this shift coincided with the financial crisis that affected everyone around the globe, including Pleyel’s high-end market. Production shrunk to just 20 instruments a year.

According to same Wall Street Journal article, Pleyel reported losses last year totaling €1.14 million ($1.53 million) on €728,000 of revenue.

What a heartbreaking ending for a piano maker known as the “Ferrari of pianos.” Pleyel history is long and celebrated but not without challenges, as revealed in The Pleyel Story. Founded in 1807 by Ignaz Pleyel, an accomplished composer and musician who studied with Joseph Haydn, the company was once legendary for its renowned clientele. Pianos were custom made for the likes of Frédéric Chopin, Claude Debussy, Franz Liszt, Maurice Ravel, and Igor Stravinsky.

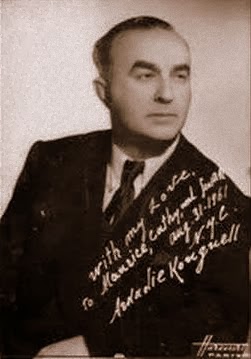

Little did I know that, just a few miles from my home, stands a custom–made Pleyel baby grand piano. In the early 1930s, it was built for one Arkadie Kouguell, a child piano prodigy, whose long and illustrious music career began at the tender age of nine years in Russia, spanned the continents of Europe and Asia, and eventually moved to New York City from where, years later, the piano would make its way to the home of his granddaughter in Stratham, New Hampshire where Poole tunes it.

Susan Kouguell inherited the Pleyel from her grandfather upon his death in 1985. With this gift, came legions of stories about the man who played this beloved piano for more than 50 years. Susan was kind enough to share some of them with me last week.

In 1919, during the Bolshevik civil war, Kouguell, his wife Marie, and son Alexander emigrated to Constantinople, Turkey, where they lived a short time before moving to Beirut, Lebanon, where they lived for nearly 25 years. He founded the music department at American University and was made director while he continued to tour as a concert pianist. In 1930, Maurice, Susan’s father, was born in Beirut and, around this time, work commenced on what would surely be one of the elder Kouguell’s dearest possessions, the Pleyel baby grand.I asked Kouguell why her grandfather chose a Pleyel. She said she didn’t know for sure but that her grandfather was “very particular” and that “he must have really liked it or he wouldn’t have bought it.” “He was very particular…in a good way,” she added. I guess he did indeed like it as it stayed with him for the rest of his life.

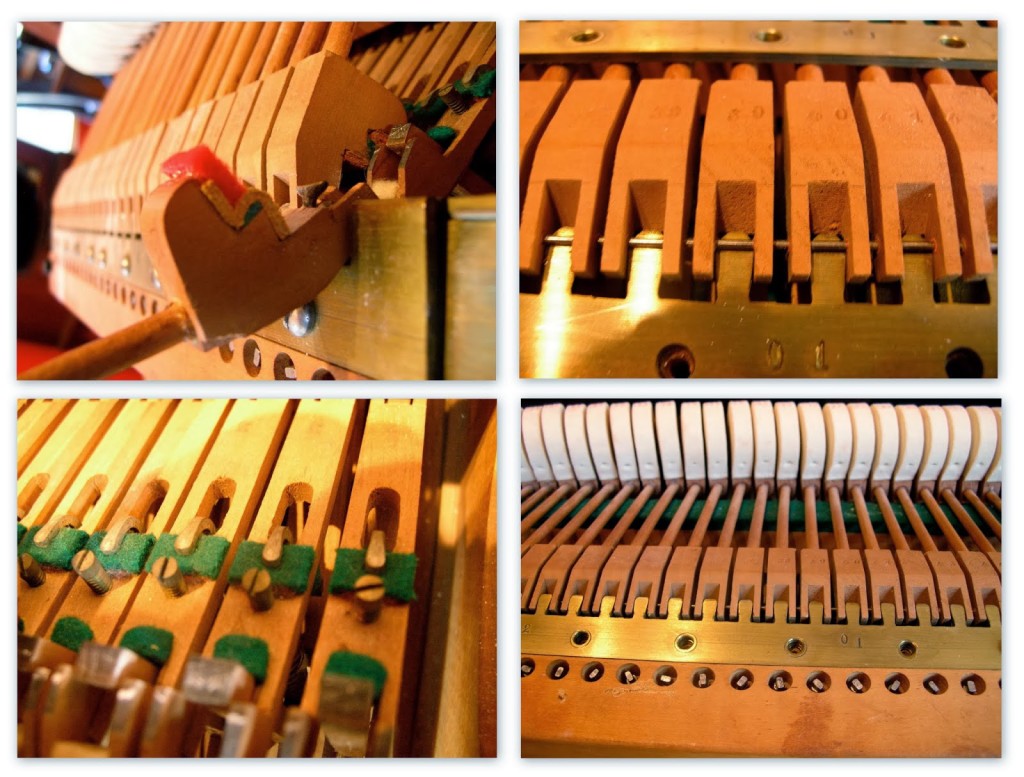

To build a Pleyel is a labor of love. There are upwards of 5,000 different parts in a Pleyel piano, requiring as many as 1500 work-hours and about 20 expert craftsmen for each piano.

After WWII, the family moved to Paris. They were forced to flee, according to Robert Azzi, close friend of Maurice (Susan’s father) in Exeter, New Hampshire. In a recent article, Azzi wrote that “…Lebanon was not a comfortable place for a Jew to be after World War II, when the modern state of Israel was being created and the surrounding Arab states were in turmoil….”

In Paris, Arkadie continued to work with the École Normale de Musique de Paris, the conservatory with which he had established a relationship as early as 1928. (Both sons studied music there, too: Alexander studied the cello and Maurice studied the viola.) Marie certainly continued playing the piano although it doesn’t appear that she continued to study music in any formal sense.

The musical pedigree that this family of musician prodigies had established by this time was formidable by any standard, and I can’t help but imagine that it must have been as intimidating as it was fascinating to the next generation. Ah, the pressure of having so much musical brilliance coursing through one’s veins….

In the early 1950s, the Kouguell family moved to New York City. There, the elder Kouguells taught piano to aspiring players and, for Arkadie, composing became increasingly important. Susan was born in New York City to Maurice and his wife Kathi. Susan spoke very fondly of frequent visits to her grandparents’ Upper West Side home where the two long-time concert pianists played simultaneously on pianos that sat side by side. Her father used to tell Susan stories of listening to his parents play the piano in Beirut, many years earlier, often sitting underneath the piano when famous musicians—Arthur Rubenstein, for example—would drop by for, perhaps, some “salon music,” a genre that Chopin fancied and probably played on one of his Pleyel’s back in the early 19th century. Clearly, Arkadie Kouguell’s Pleyel was a central part of this close-knit family’s life, across the generations.

Music was very much a part of Susan’s own childhood home, too–her father, after all, was a very accomplished violist. However, his career veered away from music toward psychology: he was a school psychologist and had a private practice that focused on clinical hypnotherapy but he remained a life-long chamber music player. He died in 2008 in Exeter, New Hampshire. Susan’s mother, an artist known for her mixed-media work, studied in New York with some of the most accomplished artists in that genre. One of her solo exhibits, according to a New York Times review, was inspired by a 13-page letter that her father wrote, “describing his family’s experiences in Germany and the Netherlands during the Nazi era.” Entitled “My Father’s Words: Let the Houses Be the Witnesses,” it was exhibited, for example, at the Holocaust Museum in Long Island, and, locally, at Phillips Exeter Academy’s Lamont Gallery in Exeter, New Hampshire, where she lives. Susan’s uncle, Alexander, continued to study the cello and today, at 92 years old, has a resumé with a depth and length that would impress even the tough critic I suspect his father was. He lives in Queens.

Susan chose to play the viola, like her father, and my guess is that she is quite accomplished. Not surprisingly, she also dabbled in piano playing when she was in high school, “mostly for music theory purposes,” she said. However, Kouguell’s career, although in the arts, does not focus on music. She is an award-winning screenwriter, filmmaker and teacher of those subjects at Tufts University with a list of accomplishments way too long to mention here. Just a few tidbits from that very long list include having six short films in the archives of the Museum of Modern Art (one of which went to MoMA’s permanent collection), having worked with French director Louis Malle, and a whole lot of published work about screenwriting (e.g., most recently a book entitled Savvy Characters Sell Screenplays!).

The piano would clearly be in the custody of another extraordinary Kouguell. Susan took ownership of the piano in the mid-1980s when her grandparents passed away but it would reside in her parents’ home until she had a room large enough to accommodate it. Today, the famed Pleyel rests in Susan’s home in New Hampshire where the third and fourth generation Kouguells can enjoy it.

“It’s a beautiful instrument,” Susan said.

Poole, tasked with tuning the Kouguell’s piano, concurred. “It’s a very pretty piano,” Poole said, but “I’ve never seen action like this.”

“Tuning this piano is both interesting and challenging,” Poole elaborated.

“The distinctive aspect of this piano, from a technician’s standpoint, is the action design which is very different from that of modern day pianos,” Poole said.

“The piano has a very nice tone,” Poole said, “a very nice sound.”

“It’s a distinct tone,” Susan said. “A Steinway sounds, well, ‘bright’ and, to me, the Pleyel sounds mellow and pure.”

“It’s deep warm tone blends well with the viola,” Susan added.

The piano continues to be played not only by the family, but by other pianists with some fame, as it has long been accustomed. One such pianist is Yeou-Cheng Ma, who is the Executive Director of the Children’s Orchestra Society in New York as well as a developmental pediatrician at New York’s Albert Einstein Medical Center, and, of course, Yo-Yo Ma’s sister. Another pianist who often plays this Pleyel is local resident Mary Towse-Beck, who studied at the Eastman School of Music and received her Bachelor’s and Master’s degrees in piano performance from Indiana University, went on to study with some of the most renowned piano teachers in the States and in Britain, and to perform in those countries as well as across Europe and Australia.

Arkadie Kouguell’s beloved Pleyel piano, crafted over eighty years ago, lives on. Perhaps having absorbed the spirit of its original owner, with whom it traveled around Europe and across the Atlantic to New York, it seems to have taken on a life of its own.

“Everything revolves around the piano,” Susan said.

I imagine that being the keeper of such a magnificent instrument is both an extraordinary gift and a unique responsibility. There’s so much family history embedded in that 5-foot, 3-inch-long baby grand and yet upwards of 5,000 parts to care for so that future generations will inherit both the stories and the piano. Although Susan and I did not discuss these dual roles, I could hear that she understood the significance of both roles and embraced them.

I concluded my conversation with Susan and returned to my own piano, a Kawai baby grand that dominates the living room of our 18th-century home. Yes, our piano was made in Japan and is part of a category of piano that some pundits argue ultimately contributed to the closure of Pleyel; but I assure you, as much as I love our piano, it is by no means in the league of a Pleyel piano.

This is the second baby grand to occupy this place in our living room. Our lessons began on a very old Schumann baby piano inherited from my husband’s parents who had inherited it from his maternal grandparents. Already on its very last legs, my daughter and I began our piano lessons on it but, with gentle nudges from both our teacher and tuner, we realized that we really should purchase another piano. In 2004, we did and continued our lessons (and sounded much better!).

As the years passed, things changed; our piano teacher retired, our daughter focused on other interests more intrinsic to her personality (like soccer, squash, crew, art, and writing), and I, too, began to pursue other interests (such writing, squash, and traveling). The piano’s silence seemed deafening and, in one of my rare, solely rational moments, I sold it.

The moment I made the arrangements, I regretted my decision and when the piano left our home, I simply couldn’t be there to witness its departure. I returned to a living room that felt empty and bereft of spirit. Days passed and I didn’t feel any better. I thought I had made a sensible decision but decisions that are based solely on what may make sense often don’t enrich our lives.

Our daughter returned home for Thanksgiving break—just a year ago, actually—and was heartbroken to find the piano missing. In spite of walking past it without stopping for years, she was, she explained to us, intimately tied to it. All those Monday nights, all those hours practicing, and all the times our friends’ fingers graced the keys meant far more to her than I had realized.

On Thanksgiving Day, I called the owner of the piano store that had purchased it and bought it back. Our piano would have an encore, for which I will always be grateful.

I still don’t play it as much as I would like but I haven’t abandoned the idea of more concerts in our living room (as evidenced, for example, by our Edith Piaf concert with Ray DeMarco playing the piano). I have jettisoned the idea that I will ever progress past plucking the keys to produce some faint melody only I usually recognize. But, that’s okay–I have other aspirations.

As Carhart demonstrated in The Piano Shop on the Left Bank, even the most unassuming sign—in my case that small Wall Street Journal article entitled “French Piano Maker Pleyel Plays Its Final Tune”—can lead to very interesting and unexpected places. In this case, I had the real pleasure of meeting Susan Kouguell and learning about the history of her grandfather’s Pleyel piano, and I had the opportunity to contemplate the twists and turns of life’s paths and the role of serendipity. Isn’t it interesting that the day I interviewed Susan was the anniversary of her grandfather’s death, twenty-eight years earlier?

Perhaps we can harbor the tiniest hope that Pleyel will have an encore. According to the Telegraph, France’s government introduced a €380 million “economic resistance plan” to prevent further plant closures. According to the Wall Street Journal, the French Industry Minister Arnaud Montebourg intends to meet with Atelier Pleyel to discuss ways to keep their door open. In the meantime, there is apparently enough inventory to meet orders already placed.

of a 1928 Pleyel grand piano will live on!

What an absolutely beautiful story… thank you for this Susan!

Speaking of screenplays, this would make an interesting one. Haven't seen anything on French news regarding the closing but a couple of articles dated from mid-November. You'd think there'd be more of a media hoopla. You gave me a flash from the past. I'd completely forgotten having read The Piano Shop on the Left Bank! Must rummage through book cartons and see if I can find it. Thanks for this post and, once again, impressive sleuthing, Nancy.

Hello, thanks for your article, I am a piano teacher and continued my piano studies in France. I am very sad of the closure of Pleyel. I created a facebook page for support against this closure, and a petition is running on facebook. If you want to join us in supporting Pleyel, it will be a great pleasure! Feel free to share these internet pages! Thank you again!

http://www.petitions24.net/non_a_la_fermeture_de_la_manufacture_de_pianos_pleyel

https://www.facebook.com/pages/Contre-la-fermeture-de-la-manufacture-de-piano-Pleyel/1382015245375970?fref=ts

Susan – this is a wonderful article and I am glad it ends with a note of hope – that the government is trying to help. This would be a real loss for the musical community. I am glad to see others are as impassioned as you! I plan to join the Facebook group, as well. ~ David

Susan, – Your love affair with that beautiful piano was so touching. It was so beautifully written that I'm certain a few tears will be shed while reading it.

It would be so gratifying to flash forward a hundred years and find that beauty stilll in the family, all polished up and without a scratch.!

Thanks for a lovely story that will bring back memories for your many readers.

Kathy, Thanks for your note here. This article was very rewarding to write. Learning about the Kouguell family was so interesting as well reading about the history of this lovely piano. Talking with Susan was a real treat!

Yes, what a movie this story would make! I dug out my copy of The Piano Shop and would also like to reread it! Thanks, Pam, for your note!

Natacha,

Thank you so much for your note and for letting readers know about the FB page and about the petition. I have visited your site and signed the petition. Please keep us posted of the progress. My best wishes for success!

David,

It looks like there is some momentum toward preserving Pleyel in some form. I will try to stay abreast of this. Thanks for your note (and for your helpful input on the post itself!).

The post did inspire a lot of conversation and quite a few emails about the pianos that readers and friends have owned. So much for gratifying than playing video games, as one person wrote to me! Thanks for your thoughtful note.