Post-impressionist artist Paul Cézanne, born in Aix-en-Provence in 1839, spent most of his sixty-six years in his beloved Aix and he died there in 1906. He grew up there, studied law at the university, took art classes at the city’s Musée Granet—even won a second-place prize for his painting at that museum—and famously painted nearby Mont Sainte-Victoire some five dozen times.

Cézanne is generally regarded as the most famous painter to emerge from Aix-en-Provence and is certainly regarded as one of the most significant artists of his time, credited with laying the foundation for 20th-century Cubism and described as “the father of us all” by Picasso and Matisse.

However, if you want to learn more about Cézanne, don’t go to Aix. Instead, find you way to New York City—before March 15, 2015—to see the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s exceptional Madame Cézanne exhibition. There, you can see 24 of the 29 portraits of Hortense Fiquet, Cézanne’s model for two decades, the mother of his only son Paul, and, 17 years after they met, his wife. These paintings, along with 14 drawings, three watercolors, and three sketch books with informal and sometimes affectionate drawings of his wife and son comprise the Met’s mesmerizing and immensely informative exhibition.

|

| Mont Sainte-Victoire. Photo by Pamela O’Neill. |

Except for Mont Sainte-Victoire, very little of Cézanne can be found in and around Aix. Yes, there is the guide entitled “In the Steps of Cézanne” which is an interesting walking tour past family homes, friends’ homes, churches, and old haunts like Café des Deux Garçons. Cézanne’s studio (Atelier Cézanne) can be visited but there’s not much point as there is none of his work and it’s a hike from the center of town (I wouldn’t recommend it) and the Musée Granet offers embarrassingly little of the native son’s work.

When we first visited Aix, some 20 years ago, we went to the Musée Granet expecting to see some of Cézanne’s work, but there was not a single piece of his work on display. Cézanne is said to have offered the museum many paintings, but the museum rejected them. The curator at the time, August-Henri Pontier, a sculptor whose work never amounted to much, infamously proclaimed that Cézanne’s work would never be a part of the museum while he was in charge.

Since that time, and especially in the last decade, the museum has apparently recognized the ignorance of its past ways. It hosted two fabulous shows, one marking the 100th anniversary of the artist’s death (2006) and another focusing on Picasso and Cézanne (2009), both of which I saw. It also acquired several Cézanne pieces, including one of the Madame Cézanne portraits, now on loan to the Met for its current exhibition, and another one-of-a-kind portrait of Emile Zola, Cézanne’s childhood friend from whom he was later estranged. There are also three watercolors of Mont Saint-Victoire; however, for conservation reasons, they are seldom on display.

So, by now you understand why I suggest that a lover of Cézanne opt for a visit to the Metropolitan’s Madame Cézanne exhibition over a trip to Aix. There are, of course, many other reasons to visit Aix-en-Provence, one of my favorite cities in France; Cézanne is just not one of them.

|

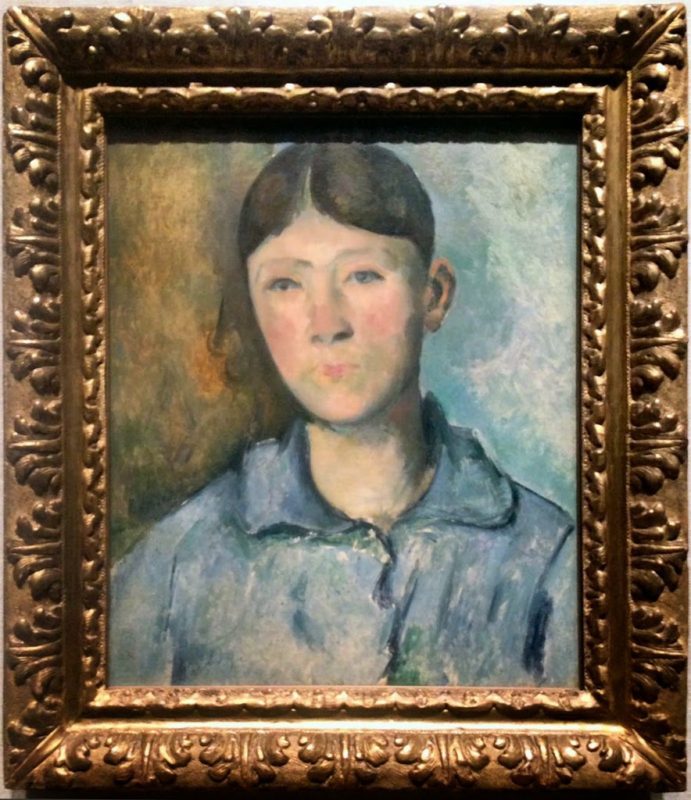

| Portrait of Madame Cézanne. Paul Cézanne ca. 1885-1888 |

The current exhibition, the first to focus on the artist’s portraits of his wife, is small but powerful. Upon arrival in the Lehman Wing, one is confronted with nearly all of the portraits displayed in one long row along the walls. My friend and I were immediately struck by how matronly, even homely Madame Cézanne appeared. Moreover, with few exceptions, any expression was utterly absent, at best, and quite dour, at worst. Did Cézanne like his wife? Was he projecting his own personality? Or, as with his still life work, was the painter’s goal to perfect his craft, to capture accurate form rather than reality and certainly rather than personality? After all, he is famously quoted as demanding that his models “sit still like an apple.” Hortense Fiquet obliged and the resulting work is both intriguing and enigmatic and, in the end, lovely. One writer likened the portraits to a Rorschach test.

|

| Young Woman with her Hair Down. Paul Cézanne ca. 1873-1874. According to the accompanying curatorial notes, this painting “is the earliest traceable painted portrait of [Hortense].” |

Very little detail is known about the relationship between the two Cézannes. They met in 1869 in Paris where Cézanne, a 30-year-old son of a wealthy banker, was studying art and Marie-Hortense, a 19-year-old book binder with a working class background, was occasionally modeling for artists. Working as a model was what brought the couple together and what would keep them tethered to one another for over the next two decades.

Their son Paul Jr. was born in 1872 but they would not marry for another 15 years or so and then only for legal reasons to benefit their son. In the meantime, Cézanne kept their relationship a secret from his family for fear that his harsh father would terminate his allowance. During this time, the couple spent much time apart from one another in order to maintain this ruse. When their relationship was made public, Cézanne’s family made it clear that they did not like Hortense. After Cézanne’s father died in 1886, shortly after they were married, Cézanne moved in with his mother and sisters and when he died in 1906, it was revealed that Hortense had been taken out of his will (but son Paul supported his mother until she died in 1922).

|

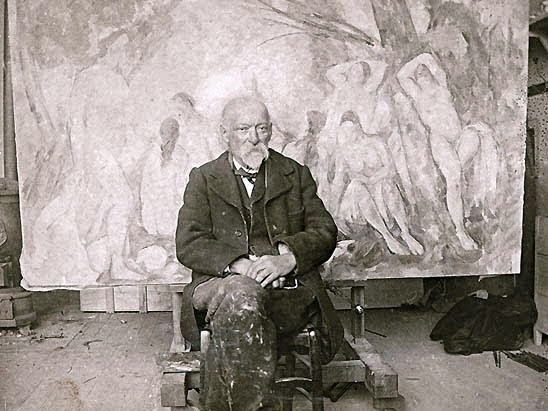

| Émile Bernard: Paul Cézanne in his studio at Les Lauves, 1904 |

Although Cézanne was known to be demanding, cranky, cold, and reclusive, little was known about Hortense’s personality and she left scant information to cast light on her nature—no diaries and few letters—compelling some art critics and biographers to rely on the face that stares vacantly from the portraits. As such an easy target, particularly derogatory characterizations were made about Hortense.

One art critic, according to the exhibition catalog, went so far as to blame Hortense for Cézanne’s mundane landscapes; in a letter to a friend, Roger Fry wrote in 1925, “Perhaps that sour-looking bitch of a Madame counts for something in the tremendous repression that took place.” Cézanne’s friends called her “La Boule,” referring to the “ball” shape of her head, as painted by the artist who was increasing focused on shapes or to a “ball and chain.”

|

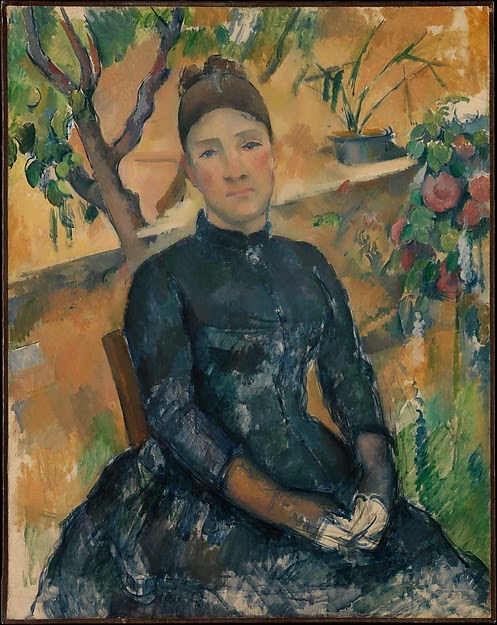

| Portrait of Madame Cézanne. Paul Cézanne ca. 1885-1887 |

So, why so many portraits? Cézanne is said to have been most comfortable painting subjects with which he was familiar. Like Mont Sainte-Victoire, a familiar presence since his childhood, Hortense certainly became familiar to the socially awkward painter and, if the sketches are reflective at all of their relationship, perhaps some intimacy had developed over the years. Maybe he was just trying to “get it right,” something he had said by way of explanation for his numerous paintings of Mont Sainte-Victoire. In both subjects, he was experimenting with form and its presentation.

Although romantic love did not sustain the Cézannes’ marriage, their strange, symbiotic partnership produced artistic masterpieces that some have argued changed the course of art history, influencing the work of Henri Matisse, Pablo Picasso, and André Derain, to name just three painters. With these 24 portraits, finally, Hortense commands the attention she deserves in an exceptional exhibition that is as haunting as it is beautiful.

|

| Madame Cézanne in the Conservatory. Paul Cézanne ca. 1888-1890. |

Notes:

“Madame Cézanne” is on exhibit at New York City’s Metropolitan Museum of Art through March 15, 2015.

Plans are underway for a larger exhibition of Cézanne’s portraiture at the Musée d’Orsay in Paris in 2017 and, later, at the National Gallery in Washington, DC.

For more information about “In the Steps of Cézanne” in Aix-en-Provence, visit the Aix-en-Provence Tourist Office.

All above photos of framed work were taken by Susan Manfull at the exhibition. All others related to Cézanne were obtained from online sources in the public domain.

We will be in New York City in less than two weeks and had hoped to go to the Metropolitan Museum of Art… now I know we'll definitely go. Thanks for this article!

Wish I could go! I will never forget seeing my first Cezanne at the National Gallery in London; Sunflowers, Van Gogh's Chair. Your article was very informative. I learned a lot I never knew. Thanks!

I love these portraits of Hortense, and think she looks quite patient. If Mark made me it that still, there would be hell to pay,

Kathy, you will not be disappointed! Let me know what you think! Afterwards, go see the Leonard A. Lauder Collection of Cubist Art, up through February 16, also an exceptional exhibition.

Sharon, So glad you liked the article and, yes, there is nothing like the arts to inspire us and stay with us forever!

Not many people could (or did) endure the long sessions Cézanne apparently demanded. I read that Cézannewould frequently take 20 minutes in between brush strokes!

Mark, I LOVED this video! To my readers: do watch at least the first 20 minutes as the narrator, Monty Don, makes his way to Jas de Bouffan (just outside of Aix) where Cézanne painted many garden scenes. I have never been there but it is definitely on my Provence bucket list now. Here is a link with information about visiting it: . Thank you, Mark!