It’s Academy Award season, and as it was with me a year ago when I wrote of Marcel Pagnol, I am drawn back to Provence, in fact to his hometown of Aubagne. On this occasion it began last fall when I was discussing with my wife Benedicte, who is French, about the genre films that Hollywood is known for which might appeal to her. In the past couple of years she has become a fan of American westerns, so I thought Foreign Legion fare could be of interest. What I quickly ran up against though was that while the western has survived successfully since the early days of cinema, little “strife on the sand dunes” has come out of Hollywood since the 1950s, and for the very best drama and action, one must go back much earlier.

As Ben is not enamored with black/white productions I was getting little traction when I urged her toward my favorites, the 1939 “Beau Geste” version with Gary Cooper, and “Morocco” (1930), again with Cooper, and the sultry Marlene Dietrich in her first Hollywood film, each of which are in my DVD film library. Laurel and Hardy’s three Legion laughers were not even worth a mention, as this funny duo fail to amuse her.

While spending a few days in Provence in late November I suggested we look into stops at the Foreign Legion vineyard in Puyloubier, east of Aix-en-Provence, as well as their Musée Legion Étrangère, which is located on the headquarters site in Aubagne, outside Marseilles. The vineyard production is sold principally at Legion bases and it provides income for the retirement home they maintain nearby. I first learned of their vineyard in a TV program several years ago, and on each return to Provence since then I have tried, without success, to make time in our schedule to seek it out. But we dropped the idea to see it when no response was received after a couple of calls were made to determine if they were open, leaving us only the opportunity to see the museum. My experience there makes me regret that I had never placed a higher value on visiting.

The French Foreign Legion was created in 1831 at the direction of King Louis Philippe. Its intent was to have a body of troops supplemental to the regular army that were formed from expatriates and colonials arriving in France. Over its history it has drawn frequently from various waves of immigrants who saw the value of paid service limited to five years. Depending on military needs its size has expanded and contracted over time, and today numbers about 8,000. At the outbreak of war in 1914 the legion was at approximately 2,500 men; two thirds were Germans and Austrians, who were placed immediately at bases in Algeria and Morocco to reduce the possibility of desertion.

The cinema, here and in France, has tended to focus on the Legion’s more dramatic engagement of lost souls and criminals escaping the clutches of justice. This is valid, although such enlistments were likely minimal; still, some unique stories have surfaced. Cole Porter claimed to have joined the Legion in Paris in 1917. Perhaps he did, as he was surely disappointed that his first musical after leaving Yale, “See America First,” closed on Broadway in March of 1916 after just fifteen performances. He would not be back with another show on Broadway, a mecca of legitimate theatre he adored throughout his life, until 1928 (with “Paris”).

As he maintained an apartment in a chic part of Paris, in which he reportedly entertained in fine fashion from the time of his arrival, I wonder to what extent he was truly attached to the military. It seems, on occasion, he did get near the front, passing out aid parcels for the Duryea Relief Organization, but I cannot imagine him serving as a gunnery training officer in the Legion, as reported in some accounts I have come upon. I saw no mention of him during my museum visit.

My motivation for visiting the museum was influenced by Hollywood melodrama, which usually depicts Legion engagements in North Africa. I had scant knowledge of their involvement in other theatres of war. My impression of the Legion in modern times is as a sort of expeditionary force sent into Francophone countries when unrest pops up. Standing in front of a panel at the museum listing fatalities in all campaigns since their formation I was surprised to learn that the costliest loss of personnel was not in either of the world wars, but rather in Indo-China. Turning toward other exhibits, I wondered if the scars of Vietnam have lingered as long for them as they have for us Americans.

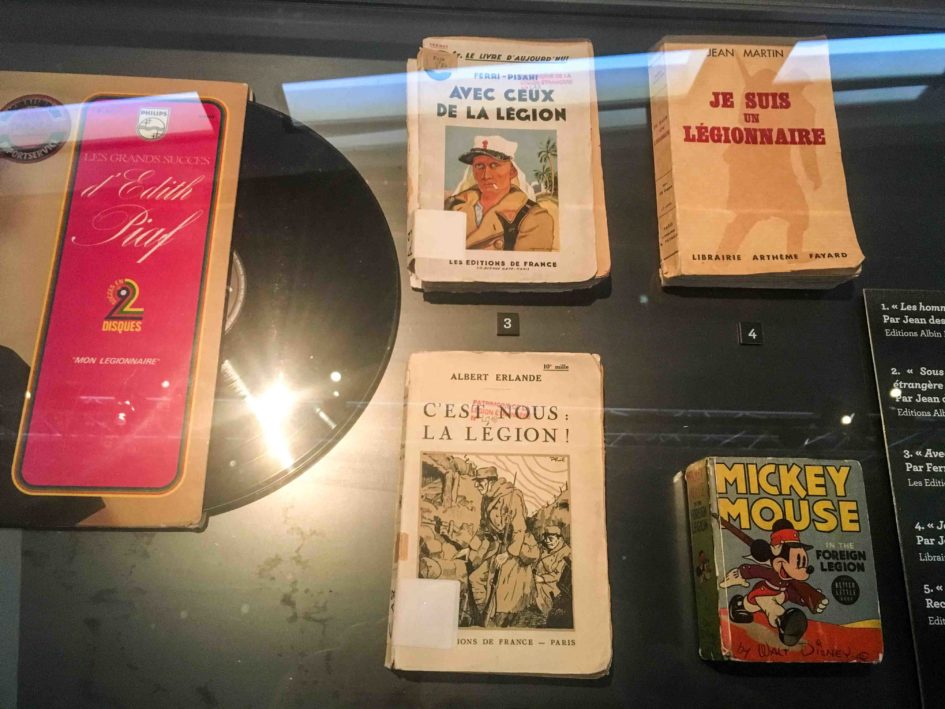

The museum is free, and the exhibits well arranged with informational panels, but only in French. (Well, there is one item in English, but I will come to that in a moment.) Immediately on entering you see the large film posters, which gave a movie buff like myself me a welcoming feel. Somehow I could not imagine a museum at an American military base organized similarly as one enters. I was especially pleased that the legendary Hollywood buffoons Stan Laurel and Oliver Hardy are the first thing encountered. Nearby, a display case presented literary works with a Legion connection, and again humor appeared, in the form of an old Mickey Mouse cartoon book.

On later reflection, I thought the curator had it right in how it begins, because once you leave that initial area the humor disappears. Get in the humor, but it out of the way early, so that you recognize that this is a serious military time capsule that pays homage to a unique corps of volunteers that have etched a record in military history. If I were tasked to encapsulate its ethos in a single word, I would select “valor.” It stares you in the face as you gaze upon the painting entitled “The Last Cigarette,” which depicts a final enemy assault upon a small unit.

The pièce de résistance is the self-made prosthetic wooden hand of Captain Danjou. It is the most important historical relic in the Legion, brought out each year from its resting place in the museum crypt for public display only on April 30, for what is termed Camaróne Day. This is to honor the memory of Danjou and the sixty-four Legionnaire’s under his command who, on April 30, 1862, while on an important mission near Palo Verde, came upon a large cavalry unit from a Mexican force of 2,000 to 3,000 that the French did not know was camped in the area.

Retreating to a walled-in hacienda named Camerón, Danjou advised his men that delaying the enemy force was imperative, and thus they must not surrender. Engagement began at 9 am, and at noon Danjou was mortally wounded. They held out for another six hours, and upon running out of ammunition, the surviving five soldiers fixed bayonets and charged out toward the Mexican force. Two were killed and the remaining three captured. Acknowledging their courage, the Mexican general ordered them to be spared, and released them. Later Danjou’s hand was found, and eventually returned. During Cameróne Day ceremonies at the base in Aubagne, the Legionnaire who is chosen to carry the glass case containing the hand is deemed highly honored by the entire force.

Although there is an emphasis on weaponry and regalia from different eras in the museum exhibits, several bottles of their wine are also on display, notably one example showing an arresting pin-up girl on the label. Reflecting on that now, creating such a design makes a great deal of sense to me: there are no women in the Legion. I liken this label to the famous photo of Betty Grable, clad only in a bathing suit. Carried by many American troops in WWII, It was a moral-booster. I doubt all the bottles were discarded after consumption as I suspect the label played a similar role.

Benedicte was taken with the Legion-inspired women’s outfit on display which was created in 1969 by Gabrielle (Coco) Chanel. My favorite costume was that worn by the pionniers (pioneers), leather-aproned, axe-wielding field engineers who are positioned at the head of the troop when they parade. I am always pleased to see them during Bastille Day telecasts from Paris. Unlike the uniforms of the foot soldiers, that of the pionnier has changed little since they were formed in 1844. Always heavily bearded, they wear the classic white Kepi (cap), white gauntlet style gloves, long handled axe, and the truly signature tan colored leather apron. As the Legion marching cadence is very slow, they are usually the last military unit appearing on July 14.

The pionnier uniform is more than decorative. Its functionality derives from their role of attacking the enemy defenses to impart room for the weapon carrying troops to advance. The apron was to protect them if they fell upon any broken pieces strewn about by their axes, and the beard, well, it seems the original pionniers would not shave until after a campaign was concluded. Eventually that morphed into the beard being de rigueur.

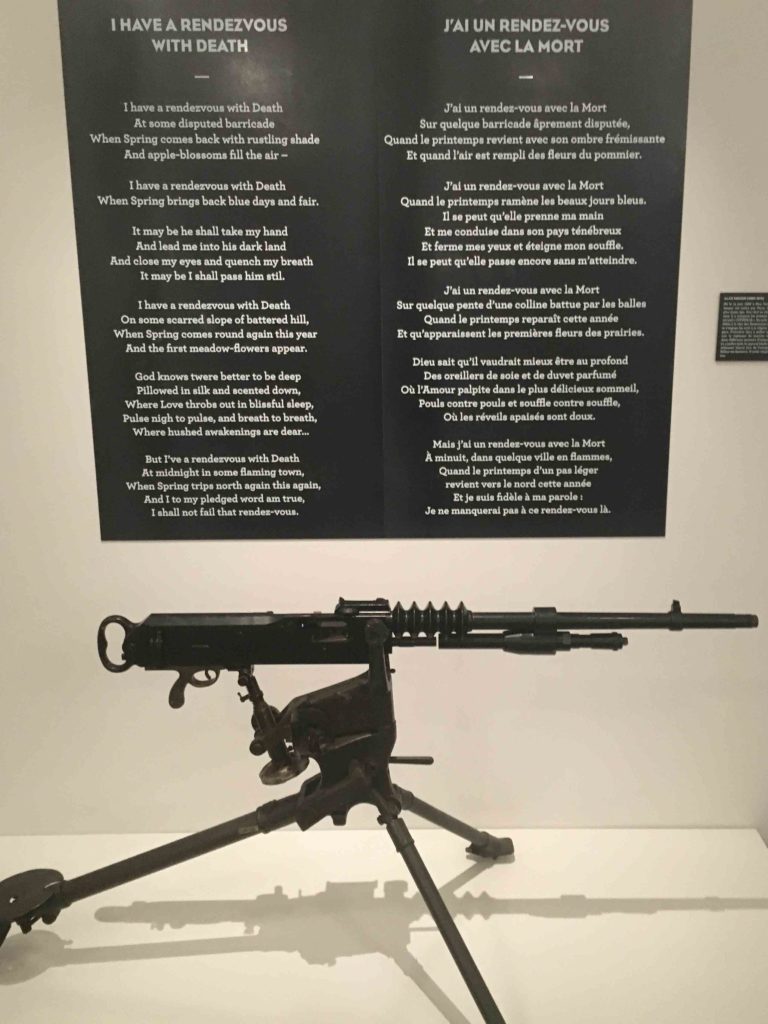

As to the only English language use in the museum, I have Google and Wikipedia to thank for introducing me to Alan Seeger, an American poet of whom I had no previous knowledge until I prepared for the museum visit. Living in Paris when war with Germany broke out he immediately enlisted in the Legion. “I have a Rendezvous with Death” was written during his service at the front. It is displayed both in English and French on a wall in the museum. I subsequently learned that this poem was a favorite of John Kennedy, who would have Jackie recite it to him.

Beneath the display is a machine gun of that era, which is fittingly placed there as Seeger lost his life by a machine gun on July 4, 1916. His unit was advancing on a town in the Somme, a major stalemate area for much of the war and site of horrific losses on both sides.

My introduction to Alan Seeger that day was the opening to a quest to know more, not just of Seeger, but other Americans who chose not to wait until a neutral America accepted that France and her allies vitally needed its military assistance, which only commenced with troops commanded by John Pershing arriving in France during April, 1917.

Three days after Aubagne, we traveled to Paris, arriving the afternoon before our return to Boston and going immediately to Place des Etats-Unis in the 16th Arrondissement. I wanted to see the monument, unveiled there on July 4, 1923, in honor of the 120 American volunteers who gave their lives in service to France during WWI. At this point I will interrupt this story, as what I saw at that little known park (which I recalled walking through by chance in 1974 but not noticing this memorial then) encouraged me to learn more of that significant moment in time which I shall report in an upcoming second installment.

Notes:

Other articles that may also interest you…

FRANCE’S FABLED FOREIGN LEGION DEPLOYED TO MALI FROM PROVENCE

This is a terrific piece, Jerry. I had no idea the museum (or wines) existed. You have me wanting to see these films, now, and I am hoping they are available on Netflix! Thanks for a good read!

David,

Good luck with Netflix. They are both worth watching, though I would give the edge to Morocco because of the magic of Dietrich under the guidance of Josef Von Sternberg. The ending is especially captivating. Do you have a DVD player?

Jerry – Beau Geste is available on DVD to rent on Netflix (yes, we have a DVD player) and is in our queue. Morocco is on their list to acquire, don’t know when. I will keep trying other outlets to see if I can find it. Thanks for your thoughts!

Thanks, Jerry. What an informative article! I did not know that the Legion was still operating. The ax wielding engineers–who knew?! And the leather apron symbolizes the pragmatic French. I assume you gathered a bucket load of post cards.

Mary,

Curiously they did not sell any postcards at the museum. Had they I would have happily gobbled them up. Same for the Place des Etats Unis in Paris, of which I will write considerably more in my follow up article.

Great piece, Jerry. Definitely a museum worth a visit for those of us who grew up with Beau Geste and Morocco. The former inspired me to read all of Percival Christopher Wren’s series of “beau” novels, Beau Ideal and Beau Sabreur, completing the set. Although his writing is quite dated now, the pulsing valor and high-minded ideas of the time can still thrill. Some of the poetry coming out of WWI, like I Have a Rendezvous with Death, is fabulous. Thanks a million for publishing this.

And thank you Jenny for letting me know of the other “beau” novels. I wonder if they led to film sequels back then? In doing the research on Alan Seeger it seems he did have a following before he perished on the battlefield. I am not sure his poetry stayed in print very long. I think he got himself to Paris a couple of years before 1914, which is considerably earlier than most American writers.